As the seconds ticked toward 1:30 a.m. on June 17, 2017, Lt. j.g. Sarah Coppock darted onto the Fitzgerald’s bridge wing.

The sea air curled black around her as she gripped the alidade, frantic that she’d be tossed overboard.

“Oh shit,” she said. “I’m so fucked.”

She didn’t know the name of the hulking merchant vessel looming out of the night off the coast of Japan, but it was the Philippine-flagged ACX Crystal, and it was going to spear into the smaller guided-missile destroyer, tearing a gash in the hull before continuing into the darkness at 18 knots.

Coppock’s fellow watchstanders on the bridge also had succumbed to “confusion, indecision, and ultimately panic,” according to an internal Navy investigation into the Fitzgerald disaster obtained by Navy Times.

Helmed by Rear Adm. Brian Fort, a surface warfare officer with more than a quarter-century of service to the Navy, the secret probe was sent up the chain of command 41 days after the collision.

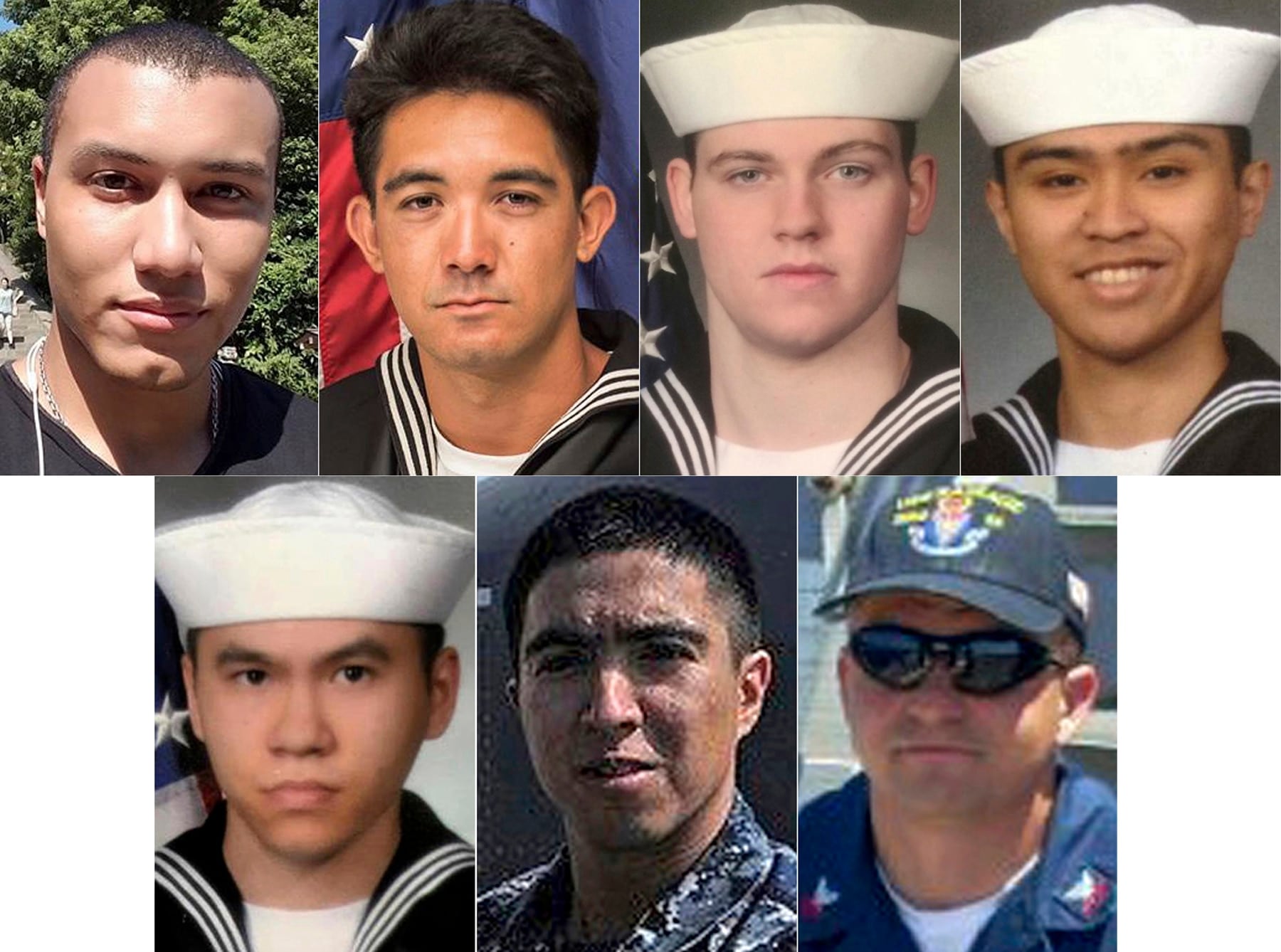

It was designed to both candidly describe to senior commanders what went wrong while helping federal attorneys defend against lawsuits from the ACX Crystal’s owners and operators and, indirectly, the families of the seven sailors drowned in the berthing spaces below the bridge.

The Navy has paraded out a series of public reports addressing both the Fitzgerald tragedy and the Aug. 21, 2017, collision involving the John S. McCain and the Liberian-flagged tanker Alnic MC that killed 10 more American sailors.

But none of those investigations so starkly blueprinted the cascade of failures at all levels of the Navy that combined to cause the Fitzgerald disaster, especially the way the doomed crew of the destroyer was staffed, trained and led in the months before it the collision.

Fort’s team of investigators described a bridge team that was overworked and exhausted, plagued by low morale, facing a relentless tempo of operations decreed by admirals far above them, distrustful of their superiors and, fatally, each other.

And Navy officials knew all of that at least a year before the tragedy.

Barreling into a shipping superhighway

Publicly released accounts of the Fitz disaster state the warship was performing routine operations at the time of the collision

But Fort’s report shows how grueling life had become for the crew and throughout the Japan-based 7th Fleet.

The crew’s workday began at 6 a.m. on June 16, 2017, and it involved “a full schedule of demanding evolutions.”

By the time Coppock and her watchstanders arrived on the bridge 16 hours later for their four-hour shift, they were “fatigued and without adequate rest,” the report states.

Although they were moving through one of the world’s busiest maritime corridors at night, neither their commanding officer, Cmdr. Bryce Benson, nor his executive officer, Cmdr. Sean Babbit, joined them.

To Fort, that was inexplicable, but he soon discovered it was a routine practice on board the Fitz, dating back at least to the warship’s previous commanding officer, Cmdr. Robert Shu.

Benson was “a little more active” on the bridge than Shu, but “it was not routine for the CO or (executive officer) to come up to the Bridge from (10 p.m. to 6 a.m.),” Fort wrote.

Out of 78 underway days from February to May of that year, the CO was on the bridge just four times between the dark hours of 10 p.m. to 6 a.m., according to the report.

In fact, both Benson and his XO Babbitt were in their quarters when the ACX Crystal collided with the Fitz.

Benson was left dangling from the splintered hull above the sea, and his sailors had to break into his room to save him.

He suffered a severe traumatic brain injury and now faces court-martial, charged with dereliction in the performance of duties through negligence resulting in death and improper hazarding a vessel.

Benson had been the XO to Shu before “fleeting up” to take command of the warship shortly before the collision. It was his first transit from Sagami Bay to the open sea as the Fitz’s CO.

Shu said in an email to Navy Times that he “visited the bridge as well as all controlling stations daily.”

“I routinely stopped by controlling stations to see how the watch was going and if the watch had any questions about anything going on,” he said. “I always reminded them to keep things safe and call if they needed anything. I routinely stopped by the bridge every night before going to bed.”

Before the collision, the Fitz was rounding Oshima Island, pointed toward the bustling sea lanes known as the Mikomoto Shima traffic separation scheme.

It’s a shipping superhighway, and the Fitz was barreling into traffic.

“Watchstanders were unaware of this approaching and dynamic change in the surface traffic pattern and sailed headlong into this crossing traffic at 20 knots,” Fort wrote.

Despite a standing order to warn him when vessels got too close to his warship, no one bothered to awaken Benson as the Fitz neared the Crystal and two other commercial vessels.

'Your people are exhausted mentally and physically.’

Coppock wasn’t communicating with her CO or his XO but she also wasn’t talking to the ship’s electronic nerve center — the Combat Information Center, or CIC.

Bridge and CIC teams are supposed to constantly share information on what they’re seeing and their sensors detecting, working together to navigate a ship safety through the night.

But Coppock wouldn’t talk with the CIC because her counterparts there “had given her bad information in the past,” according to the report.

The CIC was led by Lt. Natalie Combs. Testifying under oath at a hearing last year to determine if Combs should stand court-martial, Fort said it was “unfathomable” that the bridge didn’t talk to the CIC on the night of the disaster.

But Fort found that was far from the only fissure splitting the warship’s crew, a systemic problem of mistrust that he believed superiors failed to properly address long before the catastrophe.

Another junior officer told Fort’s investigators “she could not trust the person next to her.”

This issue had been echoed in command climate surveys by other crewmembers in both 2016 and early 2017 that should’ve been briefed up the chain of command to Destroyer Squadron 15, but Fort found that never happened.

Shu said in an email to Navy Times that he debriefed his first survey to Destroyer Squadron 15, but wasn’t able to debrief on the March 2017 survey “due to the schedule and changes.”

“The Commodore did have a copy of the survey as well and didn’t ever express any concerns to me about it,” he said.

The 2016 survey included comments showing “significant issues with communication across the chain of command, particularly levied at the (chief mess) and Department Heads,” the report states.

By the 2017 survey, those signs pointing to miscommunication and distrust had multiplied, Fort found, but there were other problems, too.

“Your people are exhausted mentally and physically,” one sailor wrote, a feeling shared by the bridge team on the night of the ACX Crystal calamity.

A ‘turn for the worse’

The 2017 survey results “identified continued and significant issues with communication throughout the command, concerns for stress being levied on the crew by the ship’s OPTEMPO, and significant concerns for the leadership and effectiveness of the Command Master Chief,” according to Fort’s investigation.

In the aftermath of the Fitz tragedy, numerous officers, chiefs and sailors voiced similar complaints to Fort’s investigators about the warship’s most senior enlisted leader, Command Master Chief Brice A. Baldwin, a career electronics technician who also had served on board the destroyer McFaul, amphibious warship Boxer and the guided-missile cruiser Antietam.

Fort’s report concluded that CMC Baldwin seemed “disengaged and/or not respected” inside the chiefs mess and the “CMC was unaware that Deck Division Sailors had had no sleep prior to standing the 2200-0200 watch on 16 June 2017 and yet were part of every evolution prior to assuming watch.”

After the collision, Baldwin was relieved of duty along with CO Benson and XO Babbitt and left the Navy.

He could not be reached for comment by Navy Times.

Appointed as the Consolidated Disposition Authority to mete out discipline in the wake of the McCain and Fitzgerald collisions, early last year Adm. James F. Caldwell ruled that Baldwin and Babbitt were derelict in their duties and issued them punitive letters of reprimand.

During Fort’s investigation, his team interviewed a junior officer who reported she was asked to fleet up to a second-tour division officer assignment on the Fitz “but she declined to do so, noting the poor command climate,” Fort wrote.

The 2017 survey results arrived shortly before Shu handed over command to his XO, Benson.

“Shu stated he was generally happy with the results and did not wish to stand up a Command Assessment Team … to conduct small group discussions with the crew following the survey,” Fort wrote.

Fort’s report faults the Fitz’s command failing to act on the “volume of comments” compiled in the 2017 survey, which “were well articulated and a clear case for change.”

“Although conducted under CDR Shu, CDR Benson was XO during the 2016 and 2017 surveys, and once in command should have been attuned to the fact that command climate had taken a turn for the worse,” Fort added.

Shu said he recalled concerns about Baldwin “but other than that there were no other comments that concerned me.”

After consulting with his junior leaders, Shu determined “that we didn’t need to conduct any focus groups on the survey we had just completed.”

“I did talk with (CMC Baldwin) and (XO Benson) about the comments in the survey regarding him and we determined some things we as the command triad could do to change the perception of the crew,” he said.

RELATED

RELATED

RELATED

RELATED

Geoff is the managing editor of Military Times, but he still loves writing stories. He covered Iraq and Afghanistan extensively and was a reporter at the Chicago Tribune. He welcomes any and all kinds of tips at geoffz@militarytimes.com.